The following is the full text of a speech delivered by Music Canada’s President and CEO, Graham Henderson, to the Economic Club of Canada on November 1, 2016.

Back in 2003, a famous Canadian recording artist had this to say when he was asked about his prospects in the new digital economy: “we are entering a golden age, a golden age.” This was an idea embraced by artists, the media, pundits, professors and most importantly, policy makers around the globe.

The reason for this heady optimism was the seismic events which were then unfolding in the online distribution and consumption of creative content. Peer-to-peer file sharing had become the default way for people to access virtually unlimited music for free, and the iPod had taken mobile digital music into the mainstream.

The artist who praised the unfolding of this golden age believed that the digital era would usher in a utopia for both musicians and the consumer. Artists would gain access on the Internet to a larger audience than ever before, and in return for the collapse of their traditional marketplaces, they would make more money from the sale of concert tickets, merchandise and other means. This was an epic leap of faith with virtually everything riding on one thing – the promise of digital technology.

The passage of time has instructed us that we might have benefited from a judicious skepticism, that we might have done well to have questioned the extraordinary promises and prognostications that were being made at the time. Had we done so, I wonder if the world in which we now live would have the characteristics that it does – a world in which the creative middle class, within the span of a single generation, has virtually ceased to exist. A world in which artists struggle more than ever before to earn a living wage and put food on the table. As they transition to the world of the self-employed “entrepreneur”, they are working longer hours and are sometimes engaged in activities for which they have little aptitude, such as data entry clerks – all for scandalously less money.

Jaron Lanier is an author, composer, computer scientist and, some say, the father of virtual reality. He is concerned about the challenges facing creators. In a recent edition of the World Intellectual Property Organization’s magazine, Lanier concluded that, “We have seen an implosion of careers and career opportunities for those who have devoted their lives to cultural expression. … Opportunities are rare compared to the old-fashioned middle-class jobs that existed in great numbers around things like writing, photography, recorded music and many other creative pursuits.”

Here in Canada, our creators, the people who build our nation’s cultural foundation and much of the intellectual property we export – are struggling, and along with them the people and businesses who support their work are struggling. Well paid jobs with benefits are disappearing and being replaced by precarious employment. Culture today, more than at almost any time in our history, is dependent on the largesse of the government.

One of the most deeply unpleasant aspects of the past 20 years has been the manner in which the gutting of the creative class, and now an entire way of life (think of youth being told they must accept a world of precarious employment), has been presented as an inevitability. At a recent round table, I sat beside a young entrepreneur who was beside himself at the idea that the Minister of Heritage was having hearings on the digital economy. For him, it was a pure and simple case of the “horse being out of the barn.” There was no turning back the clock, and no point belabouring the issue – “we’re done. This is the world we live in.”

Today I want to question that supposition. The idea that we cannot change the circumstances in which we live seems to be, dismayingly, widely held. I believe this outlook is founded on a sort of market-driven, hyper-capitalism, a debased and absolutist form of economic, technological determinism. Ayn Rand would love this; it is a sort of libertarian fantasy: the market determines how we live our lives and governments need to get out of the way – and that means us, the people. But let’s remember that we live in a social democracy – we live in a place where the people, not corporations, and not plutocrats, get to decide how to order their lives.

We must (and I include our government policy makers here) harness our imaginations. We cannot look at the world and see it only as it is. We have to be able to see it as it might and should be. And frankly, creators are really good at doing that.

Creators for centuries have fought and in some cases died to change the worlds in which they lived. Oppressive forms of employment were ameliorated; people, not corporations, gave us universal healthcare – because PEOPLE decided that THAT was the way they wanted to live their lives.

We are inheritors of this great tradition. And we can deploy it to restore the balance. Minister Joly, for example, as part of her cultural consultations, has asked us to think outside the box, to be bold and to think big. Well, one way to do that is to ignore the conventional wisdom that tells us: this is the way it has to be. And that is what I hope to do today.

But first, let’s look at how we in the creative community got to where we are today.

The foundation for most of the rules and regulations which govern our modern digital environment are two treaties adopted by the World Intellectual Property Organization in 1996: The WIPO Copyright Treaty and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty.

To help us better appreciate the magnitude of the task the negotiators of those treaties faced, we need to understand what the world looked like at that time. This was a world in which digital technologies – and their adoption by consumers – were in their infancy.

In 1996, less than 1% of the world’s population was online. If you were one of the few, it was via a dial-up modem that delivered websites at the rate of 30 to 60 seconds a page. You searched the 100,000-odd websites using AltaVista or Yahoo – Google wouldn’t launch for another two years.

In 1996, email had yet to surpass the U.S. Postal Service in terms volume of messages delivered. Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill was the world’s top selling album – though fans were more likely to purchase it from a mail-order club than an online retailer.

After the adoption of the WIPO treaties, it would be a full two and a half years before Napster appeared. It was four and a half years before the introduction of the iPod (2001), six years before the advent of the Blackberry “smartphone”, eight years before the first video was uploaded to YouTube and over a decade before the first song was streamed on Spotify.

The people setting the rules for our world were well-intentioned and clever; but the reality is that they were guessing. Now there is nothing wrong with guessing. We all make educated guesses on which we base our actions. But the beauty of our world is that with the passage of time and the accumulation of experience, we have the luxury of reassessing our situation, and adapting our behaviours when those first guesses clearly turn out to have been ill-founded. We have now had 20 years of experience with those early WIPO guesses. How are we doing?

Well, the preambles to these treaties give us an idea of what WIPO wanted to do. The people who drafted the Copyright Treaty, told us that it was designed to (1) recognize the profound impact of the development and convergence of information and communication technologies on the creation and use of literary and artistic works, (2) emphasize the outstanding significance of copyright protection as an incentive for literary and artistic creation, and (3) recognize the need to maintain a balance between the rights of authors and the larger public interest.

These are laudable goals. But very clearly everything would come down to the question of balance. If balanced correctly, the new rules would supercharge the digital marketplace – a boon to both creators and the public.

But very quickly, fissures began to appear. Technology advocates and so-called intermediaries argued that in order for the new technological infrastructure to get off the ground, creators were going to have to give up something to get something. What they would give up would be copyright payments that would otherwise have been required under the pre-WIPO rules: exceptions would be created. In return, creators would benefit from a larger, more diverse marketplace. So-called “middle men” would disappear. All manner of economic miracles would take place. It would be win-win.

So when the first major country to implement the WIPO Treaties, the US, did so in 1998, the intermediaries and other technology companies insisted on a quid pro quo: a series of “safe harbours” from liability. These safe harbours were codified in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and subsequently served as a template to legislators around the world. Almost every exception excused someone from making a payment to a copyright owner that they would otherwise have had to make. But there was also a social quid pro quo that was articulated over and over and over again: creators would be better off. In my view this amounted to more than a bargain, more than an article of faith: it was a social contract. A bargain which very quickly turned Faustian; a social contract that is now in a shambles.

The French economist Olivier Bomsel was among the first to call this arrangement out for what it was – a massive system of cross-subsidies. By foregoing money otherwise payable to them, the creative community would subsidize the development of the technology infrastructure.

Up to this day, much of the policy-making regarding copyright law continues to be driven by the popular mythology that digital technologies and platforms produce lucrative new opportunities for the creative economy.

Until very recently, however, the hypothesis that digitization and the Internet would unleash a Golden Age for the creative economy had not been adequately put to the test. Music Canada decided to address this information gap by commissioning an independent analysis to measure the impact of digitization on the creative economy.

The author of this study is Dr. George Barker, Director of the Centre for Law and Economics at Australian National University, and currently a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics. His paper examines the data on the effect of digitization and the Internet on among other things, Canadian music industry sales.

The paper seeks answers to the questions, “Have digital technologies and the Internet –together with the copyright liability exceptions adopted to spur them — spawned a Golden Age for creative content?”, and “Has the need for intellectual property protection fallen in light of these benefits?”

The answer to both questions, according to Dr. Barker, is no. His study found that digital technologies and the Internet were associated with sharply reduced demand, prices and sales, and consequently, to lower investment and employment.

The evidence he cites overwhelmingly supports this finding, and here are but two examples from music:

- Globally, music sales fell about 70% in real terms between 1999 and 2013.

- In Canada from 1997-2015, music revenues fell to 20 percent of what they would have been had they kept pace with inflation and real GDP growth – a modest expectation, to say the least. This resulted in a cumulative revenue gap of over 12 and-a-half billion dollars.

Put another way, over 12 and-a-half billion dollars that would have gone to artists and rights holders simply disappeared. Most remarkably, this happened at a time when music consumption rose to record levels.

As music was gaining in value and use to the consumer, its value to the creator was going into sharp decline.

Francis Gurry, the Director General of WIPO, decried this phenomenon, concluding that the migration of creative works from analog formats and physical distribution to digital technology and internet distribution had been accompanied by an “avoidable and inappropriate loss of value to creators, performers and the creative sector.”

At least for musicians, a key component of the social contract was that while the market for the sale of music might decline, new and different income sources would arise. Infamously, this came to be associated with the idea that touring and merchandise income would supplant the sale of music products. It has not. If there is a Golden Age, it has eluded a new generation of musicians.

It comes as no surprise then that, in 2011, the average artist in Canada earned about $7,200 per year from music-related activities, according to a 2013 study conducted for the Canadian Independent Music Association. This reflects the sharp erosion of the ability of artists, especially young ones struggling to build a career, to earn a living from their creative work.

As alternative income sources failed to appear, a new and offensive concept has appeared: the idea that creators have an inner compulsion to create, and that remuneration is not integral to the creative impulse – an idea which reached its nadir in Amanda Palmer’s remark that musicians would be happy to perform with her for “beer and hugs”.

Musicians aren’t the only creators feeling the pinch. According to a 2015 survey by the Writers’ Union of Canada authors are earning 27% less from their craft than they did in 1998, after taking inflation into account.

The survey also found that median net income from writing was less than $5,000 and the average income was about $12,900 – far below the average Canadian income of $49,000. More than 80% of writers earn an income from their writing that is below the poverty line!

Creators are not alone in their struggle to stay afloat in the new economy. Taking a broader view, British economist Guy Standing argues that technologies are disrupting the way income and earnings are distributed. In his new book, “The Corruption of Capitalism,” Standing describes the appearance of a new “rental wedge” “between profits, which are growing, and ever more concentrated, and wages, which are falling and ever more uncertain.”

The “Precariat,” as he calls the new social class, is “defined by the insecurity and instability of the work it performs.” He identifies them as “Uber drivers, millennial interns, part-time lecturers and the cleaners and couriers of the ‘gig economy’.”

Creators belong on this list as well – as its charter members, I would argue. I have heard corporate executives and government policy makers discuss the “gig economy” in almost breathless terms – invariably the people extolling its virtues have full time jobs with benefits and pensions. They have no IDEA how desperate life in the gig economy can be. Musicians know.

All of this is taking place in an environment in which music is generating fabulous amounts of money. It is just that, as Gurry points out, very little of it seems to be finding its way on to the creators’ side of the ledger.

Part of the problem has to do with how people are consuming music online. There are two principal methods – subscription and ad-supported. It is the latter — ad-supported, on-demand music services such as YouTube and SoundCloud — that have driven most of the increase in digital music consumption. But those services deliver far less revenue than paid services.

A subscription service, such as Spotify for example, returned $18 (US) a year per consumer in 2014 — compared to YouTube’s $1. Ad-supported services, with more than 13 times more users than paid services, delivered less than one-third as much money to artists and other rights holders.

The effect of this gaping disparity is that overall digital music revenue growth has lagged far behind consumption.

This disparity has been dubbed the “Value Gap” – which we define as “the gross mismatch between the volume of music being enjoyed by consumers and the revenues being returned to the music community.”

So where to from here? What can be done to restore the creative middle class and level the playing field?

As I noted when I began, we are fortunate in Canada to live in a well-functioning social democracy. We can make choices about the type of society we live in, and collectively, through our political representatives, we can take action.

Music Canada is among those now calling for reforms. But the entire creative community, here in Canada and around the world, is speaking up.

The Writers’ Union views the situation we face as nothing less than “a cultural emergency for Canadians.”

“If we want a strong and diverse publishing and cultural industry, it is essential that creators are reasonably and fairly compensated,” it argues. “If writers continue to be compensated … at these low rates it will inevitably become impossible for professionals in the field to earn a living.”

This year in Europe and the US, thousands of artists have petitioned their governments to address the value gap and rebalance the rules. Expect more of the same, very soon, in Canada.

There is very clearly a call to action – so what should this action look like?

Well for a start, any approach to the problem should be holistic and multijurisdictional.

Music Canada has been aggressively opening new channels to do this. For example, we have been taking the message to municipalities that they can implement simple, straightforward local policies to improve the business environment for creators and the businesses that support them.

Music Canada identified these options in our 2015 Music Cities report. The report has gone viral all over the world.

The idea of local governments creating music cities, and mayors running on pro music platforms, would have been ridiculous just a few years ago. Yet today nine municipalities of various sizes across the country have Music Cities strategies in place. And more are coming.

Municipalities are taking these steps because they understand that the benefits are worth the effort. For example: job creation, economic growth, tourism development, city brand building, artistic and cultural growth. Strong music scenes have also been proven to attract other business investment along with talented young workers who put a high value on quality of life, no matter what their profession is.

At the provincial level, Ontario and BC are trailblazers, having created music-friendly programs that are almost unique in the world, with substantial music funds and music-friendly policies such as red tape reduction strategies to facilitate live music performances.

For her part, Minister Joly has been crisscrossing the country, asking people to think big, to be ambitious and to step outside the box.

So let’s think about that. How CAN the federal government get involved? How can it innovate and, like Ontario and BC, blaze a new trail? The government has made it clear that it wants a new toolkit to confront the challenges facing Canada’s creators, that it seeks a new social contract.

It has four levers in its toolkit: legislation, program funding, policies and treaties, and institutions. Here are some thoughts about how those levers might be pulled to benefit our creative community.

Legislation

This one is simple. End all the cross-subsidies paid by creators. Now.

The businesses that benefit from these cross-subsidies have become wealthy beyond imagination over the years. The goal initially was to get them off the ground. Job done. The creative community has been making its contribution for two decades. It’s payback time.

Policies and Treaties

First, I’d like to applaud the federal government on signing the CETA agreement with the European Union. This treaty contains provisions that will encourage the creation of intellectual property assets. The production of these assets results in a double dividend for our country – 1) they are material assets, which are owned by Canadians and are exportable, and 2) they are cultural – assets which allow us to tell our story to the world. More of this please!

Second, I note that Ontario, BC and municipalities across Canada are all designing policies to attract foreign direct investment in the domestic music economy. The federal government would do well to heed those examples, and pitch in with supportive policies of its own.

Third, Canada is home to one of the most vibrant live music scenes in the world. Provinces and municipalities are awake to the music tourism opportunities this presents. This is an easy one Ottawa: tell the rest of the world what a brilliant destination we are for music tourism; market music! Brand Canada as one of the greatest live music scenes in the world, and brag about it!

Program Funding

Canada currently boasts an enviable system of programme funding for music. But that funding needs to keep pace with inflation as well as the changing realities of the marketplace and creators’ lives. I have repeatedly urged the government to pay attention to how the lives of creators have changed. For example, in a globalized market, developing export opportunities is critical for them. So? Spend money on the Trade Routes programme – a LOT of money; earmark some of it for music.

Next, artists’ incomes have cratered. What could that mean? Well, how about the fact they can’t afford homes. Housing affordability has become an increasingly urgent issue for them. The federal government should seriously examine this issue in the context of cultural infrastructure. And by the way, Ontario? Get with that as well … cultural infrastructure has to be part of your infrastructure spending.

Musicians used to be surrounded by a universe of enablers and supporters. They are gone with the ecosystem, gone with the money. Musicians are now more-often-than-not micro businesses, sole proprietors, entrepreneurs. Has any thought been given to a programme to fund skills and entrepreneurial training?

Institutions

Here, the federal government has already taken positive steps such as increasing funding for the CBC and the Canada Council for the Arts. During her recent consultations, Minister Joly made the point that the government is looking to go in new and bigger directions. She looked back to an era in which the CBC, the CRTC and the Canada Council had been created.

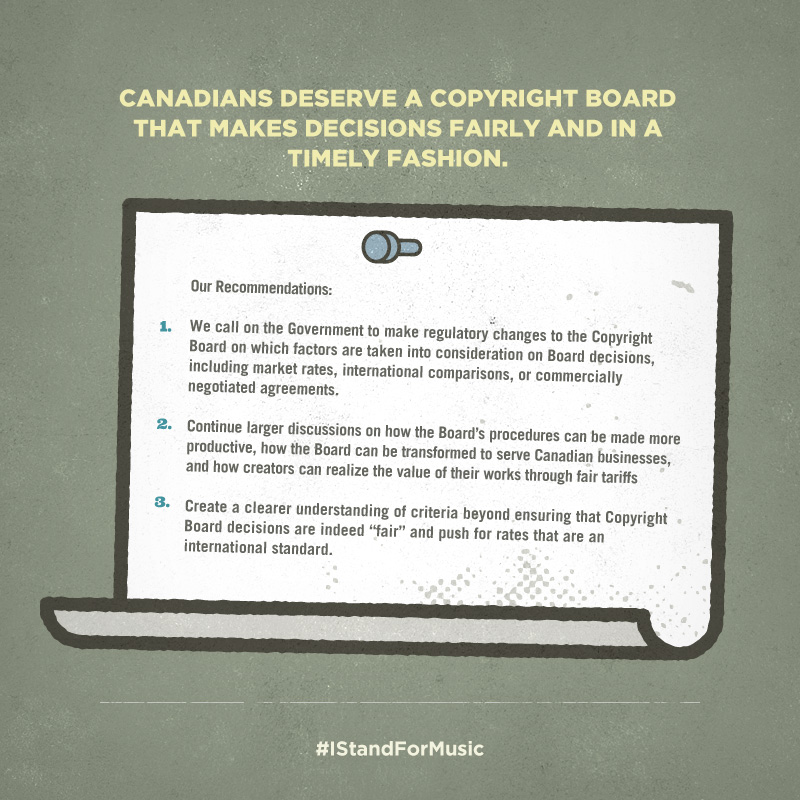

First, one institution that needs to be repaired is the Copyright Board of Canada. I’m actually flying tomorrow to hearings that are being conducted by the Senate into the operation of the Copyright Board of Canada. That is first on our list of institutions I would encourage the government to modernize, and to turn it into a true business development office for the creative industries.

But here’s a really big idea. Right across the country music education is in jeopardy. Increasingly, the students with access to music education are from more affluent communities. Inner city youth, remote, rural and indigenous communities are getting shut out. But it is not just music, it is the liberal arts in general that are at risk.

We need to reconnect our young people with the importance of a liberal arts education, with the importance of creativity. One of the things we’ve seen is an erosion of respect for the creative process. Rebuilding respect for the humanities will assist us in rebuilding our shattered framework.

The federal government needs to exercise a leadership role because this is a national issue of national importance. The federal government already supports a programme like this – focused on science. It is fantastic and connects young people with the importance of a science education. If Science then, why not Humanities? I urge the Department of Heritage to convene an expert panel to consider this issue and to establish a permanent National Humanities Council.

CONCLUSION

I will offer a sort of coda at this point. One of the questions being asked by the Minister of Heritage is “how can the government use content to promote a strong democracy?” This got me thinking about the intimate connection – throughout history – between creators and democracy. Poets, film-makers, and novelists have always played an essential role in the fight for democracy and civil rights. Here in Canada we have an immediate example at hand, Gord Downie’s Secret Path. But to his name we can add Pete Seeger, Solzhenitsyn, Vaclav Havel, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Fela Kuti and many, many more. These are all people who were banned, exiled or jailed for their fight for justice and democratic principles.

It is instructive, is it not, that after the revolution in Czechoslovakia, the people turned not to a strongman but to a playwright. A playwright whose velvet revolution had been powered by illicit tapes of Lou Reed’s band, The Velvet Underground.

As you may have heard when you entered the room, our background music was a selection of protest songs. That has been one of music’s great contributions to our world: music and protest anthems have been associated with just about every social change for decades. I’ve put a Spotify playlist together which you’ll find at your seat.

Our creators are truly, as Shelley famously said, “the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Now when he says they are legislators, he doesn’t mean they’re lawyers, he doesn’t mean they’re necessarily politicians. What I think he is saying is that creators predict our future, they underpin our future, and they create a framework (political AND cultural) for our future. To the extent we allow those voices to be in any way compromised or marginalized, our democracy will suffer a great loss.

Should we just “get used” to the way things are? The people opposing the brutal child labour regimes of the 1st Industrial Revolution did not “get used to” those conditions – they fought to change them – and they changed the world. We’re are in the midst of what some are calling the 4th Industrial Revolution. Young people today, and creators, members of the “precariat”, are also objecting to the circumstances of their lives. And I warrant they will fight to change them. As I said at the outset, in a social democracy we do not have to get “used to it”. We have the right to decide what sort of world we live in.

So my answer to the Minister’s question is this: If you want a stronger democracy that is less vulnerable to special interests, do everything in your power to restore balance to the world in which our creators live. Encourage and enable them. Our creators are not living in a golden age. That was the original goal, they didn’t get it, the promise was broken – so we owe it to them. Now.

And let’s all remember, the fight for democracy and justice has always had a soundtrack.

Music Canada